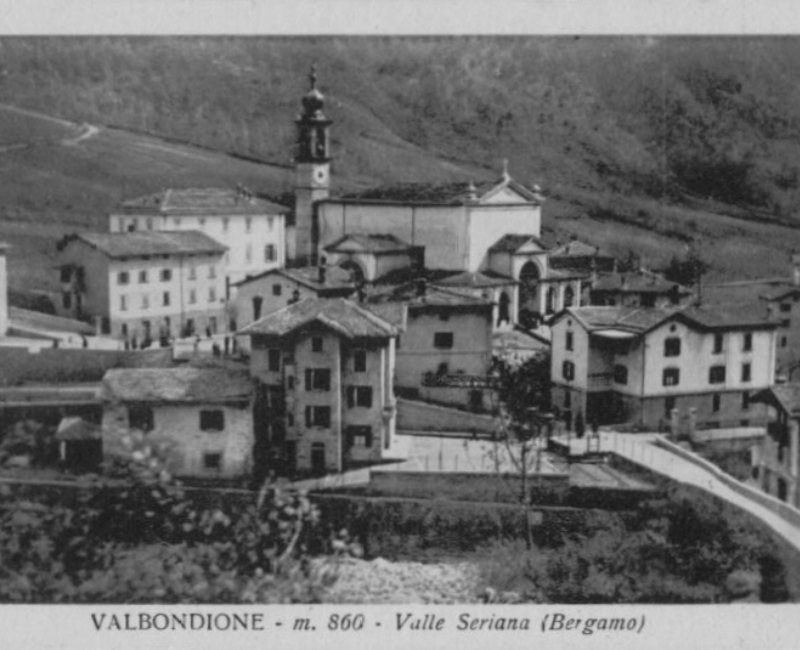

Valbondione prende il nome dal principale affluente del Serio, il Bondione.

La prima volta che questa denominazione compare è in un

documento del 774, firmato da Carlo Magno.

In questo documento Carlo Magno dona alla canonica di Thours (parigi) terreni e pertinenze che si trovavano in Bondellionem ed in val di Scalve.

Etimologicamente questo nome significa “convalle,

conca, recesso di montagna”.

Per lungo tempo Valbondione appartenne alla comunità di

Scalve poi una sorta di autonomia economica fu dichiarata nel 1202 con la formazione del comune dei 10 denari che comprendeva alcune delle contrade principali con esclusione di Bondione e Fiumenero.

Nel 1779 la Grande comunità di Scalve suddivise i suoi beni tra le diverse contrade (Lizzola, Fiumenero e Bondione) con l’esclusione del comune dei 10 denari che restò fino al 1806.

I primi insediamenti in questo territorio risalgono all’epoca romana. Un importante

numero di schiavi si diresse in queste zone per lavorare alle miniere di ferro

scoperte a Lizzola. Da qui le prime abitazioni che avrebbero costituito l’agglomerato urbano.

Nei secoli a seguire le famiglie del luogo traevano sostentamento dall’attività mineraria e dalla pastorizia.

HISTORY

Valbondione takes its name from the main tributary of the Serio River: the Bondione. The name first appears in a document from 774, signed by Charlemagne.

In this document, Charlemagne donated lands and properties located in Bondellionem and in the Scalve Valley to the canonry of Thours (Paris).

Etymologically, the name refers to a valley, a basin, or a mountain recess.

For a long time, Valbondione was part of the community of Scalve. In 1202, a form of economic autonomy was established with the creation of the so-called “10 denari municipality”, which included several of the main hamlets, excluding Bondione and Fiumenero.

In 1779, the Greater Scalve Community divided its assets among the various hamlets (Lizzola, Fiumenero, and Bondione), with the exception of the 10 denari municipality, which continued to exist until 1806.

The first settlements in this area date back to Roman times. A large number of slaves were brought to the region to work in the iron mines discovered in Lizzola. This led to the construction of the first dwellings, which would eventually form the town.

In the following centuries, local families made their living through mining and pastoralism.

Il cippo di confine posto sul provinciale tra Gromo San Marino e Fiumenero riporta la data 1736 e testimonia l’appartenenza giuridica ed ecclesiastica dell’alta Val Seriana alla vecchia “Repubblica di Scalve”.

Ma la storia di questo comune inizia molto prima, nel 1202, quando le contradelle del Serio furono unificate: Mola, Gavazzo, Dossi, Torre, Beltrame, Grumello, Pianlivere, Grumetti e Maslana, escludendo Fiumenero e Bondione, più grandi ed indipendenti.

Ottennero l’indipendenza dalla Comunità di Scalve, pur continuando a farne parte.

Al comune dei 10 denari venne assegnata la quota spettante dei beni della comunità in decima parte (da qui il curioso nome) e il comune si impegnava a pagare la novesima parte alle pubbliche spese.

Nel 1927 il Comune dei 10 denari si fuse con gli altri borghi, costituendo l’attuale Comune di Valbondione.

MUNICIPALITY OF 10 DENARI

The boundary stone on the provincial road between Gromo San Marino and Fiumenero bears the date 1736 and testifies to the legal and ecclesiastical affiliation of the upper Seriana Valley to the ancient “Republic of Scalve.”

But the history of this municipality begins much earlier, in 1202, when the districts of the Serio River were unified: Mola, Gavazzo, Dossi, Torre, Beltrame, Grumello, Pianlivere, Grumetti, and Maslana, excluding the larger and more independent Fiumenero and Bondione. They gained independence from the Scalve Community, while remaining part of it. The Municipality of 10 Denari was assigned a tenth of the community’s assets (hence the curious name), and the municipality pledged to pay the ninth to public expenditures. In 1927, the Municipality of 10 Denari merged with the other villages, forming the current Municipality of Valbondione.

Il fiume Serio nasce sul Monte Torena, che divide la Val Seriana della Valle di Pila.

Percorre il piano del Barbellino e si getta dirompente dando vita alle Cascate del Serio.

Le acque scorrevano naturalmente fino al 1931. In quell’anno terminarono i lavori di costruzione alla Diga del Barbellino che entrò in funzione.

Dal 1931 al 1969 le cascate scomparvero, la diga non venne aperta.

Con il Sindaco Riccardi M. Lorenzo, il 20 luglio del 1969, vennero riaperte.

Accorsero per la riapertura circa 20.000 persone. Ebbe una tale risonanza che arrivarono escursionisti a Valbondione anche nei giorni successivi.

Da allora le Cascate furono visibili almeno una volta l’anno, fino alle cinque aperture attuali.

Dal 2008, nel mese di luglio, le Cascate sono aperte in versione notturna.

THE HISTORY OF SERIO FALLS

The Serio River rises on Mount Torena, which divides the Seriana Valley from the Pila Valley.

It flows across the Barbellino flat and plunges violently, creating the Serio Falls. The waters flowed naturally until 1931. That year, construction work on the Barbellino Dam was completed and it began operating. From 1931 to 1969, the falls disappeared; the dam was never opened. Under Mayor Riccardi M. Lorenzo, they were re-opened on July 20, 1969. About 20,000 people flocked to the reopening. It was such a success that hikers continued to flock to Valbondione in the days that followed. From then on, the falls were visible at least once a year, up to the current five openings. Since 2008, the falls have been open at night in July.

Il dialetto bergamasco è un dialetto della lingua lombarda appartenente al ramo lombardo orientale.

Il bergamasco è derivato dal latino volgare innestato sulla precedente lingua celtica parlata dai Galli. Con il trascorrere del tempo ha subìto varie modifiche, le più importanti delle quali sono avvenute durante le dominazioni longobarde che hanno lasciato terminologie germaniche entrate a fare parte del linguaggio comune (ad esempio, tus e tusa a indicare “ragazzo” e “ragazza”, scet a indicare “figlio”, buter a indicare “burro”, ecc.).

I parlanti il lombardo occidentale e altre lingue gallo-italiche lo ritengono poco comprensibile poiché, nonostante alcune somiglianze lessicali e morfologiche, possiede una fonetica molto stretta e diversa da quella di lingue e dialetti circostanti.

Il dialetto bergamasco è stato a lungo oggetto di studio, di commenti e di confronti con l’italiano e con altri dialetti. Vari autori l’hanno dileggiato riducendolo, in maniera superficiale, a parlata macchiettistica esclusiva della gente più incolta e umile.

Il dialetto bergamasco è parlato a Valbondione, nelle sue diverse varietà. Ha origini antiche, è attestato nel Basso Medioevo da diversi atti di transazioni private, ma anche da alcuni componimenti poetici fatti risalire alla prima metà del XIII secolo.

In particolare poi troviamo il GAI’ Si tratta di un linguaggio particolare,ormai scomparso, come un codice parlato dai pastori bergamaschi e bresciani.

Un linguaggio criptico dove la mimica del volto integra e spiega le pause e i silenzi dei dialoganti: il gaì non si parla, si recita:

«… bisogna sentire due pastori parlare tra loro per assaporare tutto il fascino che assumono i termini gaì in simile contesto; per apprezzare la straordinaria ricchezza mimica che ne accompagna l’emissione…»

(Comune di Bergamo, Il linguaggio e la vita dei pastori bergamaschi.)

THE DIALECT

The Bergamasque dialect is a dialect of the Lombard language belonging to the eastern Lombard branch.

Bergamasque is derived from Vulgar Latin grafted onto the earlier Celtic language spoken by the Gauls. Over time, it has undergone various changes, the most important of which occurred during the Lombard domination, which left Germanic terms that became part of the common language (for example, tus and tusa to indicate “boy” and “girl,” scet to indicate “son,” buter to indicate “butter,” etc.).

Speakers of Western Lombard and other Gallo-Italic languages find it difficult to understand because, despite some lexical and morphological similarities, it has a very narrow phonetics that is different from that of surrounding languages and dialects.

The Bergamasque dialect has long been the subject of study, commentary, and comparison with Italian and other dialects. Various authors have mocked it, superficially reducing it to a caricatured language spoken exclusively by the most uneducated and humble people.

The Bergamasque dialect is spoken in Valbondione, in its various forms.

It has ancient origins, attested in the late Middle Ages by various private transactions, but also by some poetic compositions dating back to the first half of the 13th century.

In particular, we find GAI’. This is a particular language, now extinct, like a code spoken by shepherds from Bergamo and Brescia.

A cryptic language where facial expressions complement and explain the pauses and silences of the speakers: gaì is not spoken, it is recited:

“…you have to hear two shepherds talking to each other to appreciate all the charm of gaì terms in such a context; to appreciate the extraordinary richness of facial expressions that accompany their utterance…”

(Municipality of Bergamo, The language and life of Bergamo shepherds.)

Via Tarcisio Pacati, Valbondione, Bergamo

(All’interno del Palazzetto dello Sport)

Lunedì – chiuso

Martedì 08.00 – 12.30 / 14.00 – 17.00

Mercoledì 08.00 – 12.30

Giovedì 08.00 – 12.30 / 14.00 – 17.00

Venerdì 08.00 – 12.30

Sabato 08.00 – 12.30 / 14.00 – 17.00

Domenica – chiuso